The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh is a huge and impressive museum. It was formed by a fusion of two separate institutions. The first was the 19th century former Royal Scottish Museum, which is located in the building of Victorian neo-Venetian Renaissance from the 1860s and holds collections covering science, technology, natural history and world culture. The second, the Museum of Scotland, opened in 1998 in a Le Corbusier-like modern architecture by London-based Benson & Forsyth, related to Scottish antiquities, culture and history. Thus, the two highly diverse but connected buildings house a rich collection from prehistory to our present. With several stations which invite especially young visitors into active discovery, the National Museum of Scotland promises a ‘journey through the history of Scotland, the wonders of nature and diverse cultures from around the globe.‘

Interior of the Grand Gallery of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland; ElshadK [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D

In the light Grand Gallery, a cast iron construction rising the full height of the building, hidden behind the neo-Renaissance facade, you find yourself in a large-scale cabinet of curiosities from where you reach several galleries and rooms. In a juxtaposition of different kinds of exhibits from different contexts, it can be hard to choose where to start. During my visit, I focused on the section about Scottish history, situated in the new building over five levels. The rich collection presents thousands of magnificent objects spanning at least 50,000 years, from the geological beginning to contemporary times. From prehistory in the section Early People on the lowest level up to the 21st century on the highest, the curators attempt to tell the stories of Scottish history. However, this inevitably makes the labyrinthine overall display highly confusing.

About Architecture

Crossing the Grand Gallery and the room with technological breakthroughs, which have changed Scotland and the world, whilst passing exhibits like Dolly the Sheep, and entering the modern building, you feel quite lost. Instead of connecting the two diverse buildings in terms of content and interior, the newer building is rather like a transit hall and in contrast to its dominant external appearance reduced to an appendix of the older building. Therefore, the entire space of the massive building is not fully exploited, and especially the part of the exhibition on Scottish history, which after all, in the National Museum of Scotland, is too inconspicuous and rather hidden in the back of the museum. Thus, they missed the chance for a great opening or at least to integrate that part, however, they failed to make a connection between both the presentation and the buildings.

From Scottish formation to unification – Kingdom of Scots

On the first floor, the exhibition follows Scotland from its emergence as a nation around 1100 to 1707, when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland was created by the Act of Union, and an independent Scotland became history. There is loads to see and to discover, the gallery shows some of the most precious exhibits like the famous Lewis chess pieces or an oak panel from Balmerino Abbey from about 1600 which shows an unaffected local craftsmanship. Looking at it makes you think of modernist artworks from the early 20th century that might just as well have been influenced by these outstanding expressionistic figures. You will find magnificent antique brooches next to the Queen Mary Harp, standing in front of a replica of her tomb, or the Scottish maiden, an early form of the guillotine that was used between the 16th and 18th centuries.

Oak panel from Balmerino Abbey, Fife, about 1600; Foto: Nicole Guether

However, the architectural arrangement of the whole level is confusing as there are too many paths, too many side rooms which give you the feeling that you are missing something. Whilst coming from the section about Reformation and the meaning of the invention of printing, where the name of Johannes Gutenberg is not even mentioned, you find yourself suddenly in a small room with the Scottish maiden which marks the start of the Renaissance era. Going back to the time of Robert the Bruce and the legendary hero William Wallace, the missed narrative structure becomes obvious. Nevertheless, the lack of a main storyline is the only weakness of that level.

Moving up a level, Scotland Transformation takes us through the 18th century, beginning with Bonnie Prince Charlie, Rome-born pretender to the throne and romantic figure of heroic failure and leads to the early 19th century, during which Scotland began to change from a predominantly rural society to an urban, modern one.

The displays on levels 4-6, encompassing the Enlightenment, industrialisation with all its social and political developments and changings, brings up the topic of Scots abroad, which covers one of the saddest chapters in Scottish history.

A sad chapter in Scottish history – The Highland Clearances

A highly controversial topic, still, are the so called Highland Clearances, the forced eviction of inhabitants in the Highlands and western islands, which took place between the 1750s and 1880s. The violent displacement of people in favour of large-scale farming depopulated the Highlands and forced many into emigration – one important reason that there are more Scottish people living abroad than in the country itself.

With regards to the museum‘s point of view, said curator Michael Allan, it is difficult to interpret this topic in a unified manner such as a display case. Furthermore, the leak of a huge amount of Clearance-specific material, which just did not survive, is the main reason that there is not much to see. For that reason, the story is told through a variety of cases and galleries based on material produced for a specific event or individual but more in the context of social impact as a subject of self-imposed migration. However, due to its significance, the Clearances were the first act of modern ethnic cleansing and resulted in the destruction of the traditional clan society: Highlanders could no longer meet in public or bear arms, even the wearing of tartan, teaching Gaelic and playing the bagpipes were outlawed. The presentation should provide more courage in presenting that part of history as what it was: a violent chapter whose effects are still visible and which remains a part of collective memory.

A letter from a soldier – WW II

Reaching the top of the museum, we enter the latest part of history. Scotland: A Changing Nation is about the experiences of people living and working in the 20th century presented through five major themes: war, industry, daily life, emigration and politics. From a car, suffragist broaches and the tent used during the Democracy for Scotland campaign in the 1990s to poetry, music, archive footage, iconic objects and personal stories, the objects give a diverse overview of Scotland.

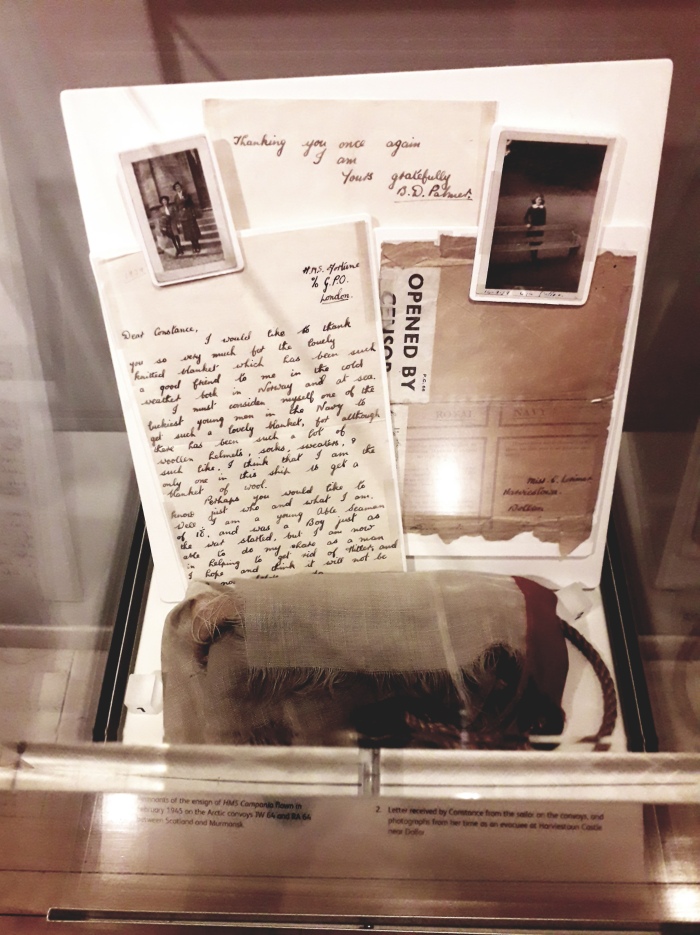

Through contemporary objects, the curators describe the impossibility of telling a complete history of the last century, a still ongoing story. The curated objects rather look at specific themes that have affected and shaped people’s lives. Due to the diversity of objects, the curators explore those themes vividly and in a visitor-friendly way. Far from being an innovative concept, however, as every museum on the globe pictures contemporary history in that way, the curator succeeds with this display because of their knack for storytelling objects. Nevertheless, by literally using everything they can the level is highly overloaded, although it is forgivable that they want to show most of their largely excellent pieces. But, let me focus on one object in particular, a letter from a young soldier during the Second World War, that is impressive for two reasons. First, the truly touching message itself, and, second, the aspect of media in context of our multimedia time.

Foto: Nicole Guether

During the Second World War, as in the First World War, there were forced ‘pen pal’ programmes encouraging civilians to correspond with servicemen and servicewomen who were stationed overseas. One of them was the 18-year-old sailor B.D. Palmer who received a letter from the 11-year-old girl Constance. The exhibition shows his reply with a still, seven decades later, heartbreaking message. Not only that the letter reflects the hope for a quick victory over Nazi Germany at the very beginning of war but also how the young were forced to grow up in times of war.

Upon request, the museum confirmed that the fate of the young soldier is unknown. Therefore, the letter that the girl then bequeathed to the museum is even more in its physical presence a timeless example indicative of the fate of many. Contemporary collecting enables to link past and present, and records those deeply personal stories. In terms of media, the simple fact of showing a letter makes us think about what one day will remain from our time?

National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh

Pingback: The National Museum of Scotland permanent exhibition on Scottish history – by Nicole Guether – nicoleguether